What Does Drug-Induced Mitochondrial Dysfunction Mean?

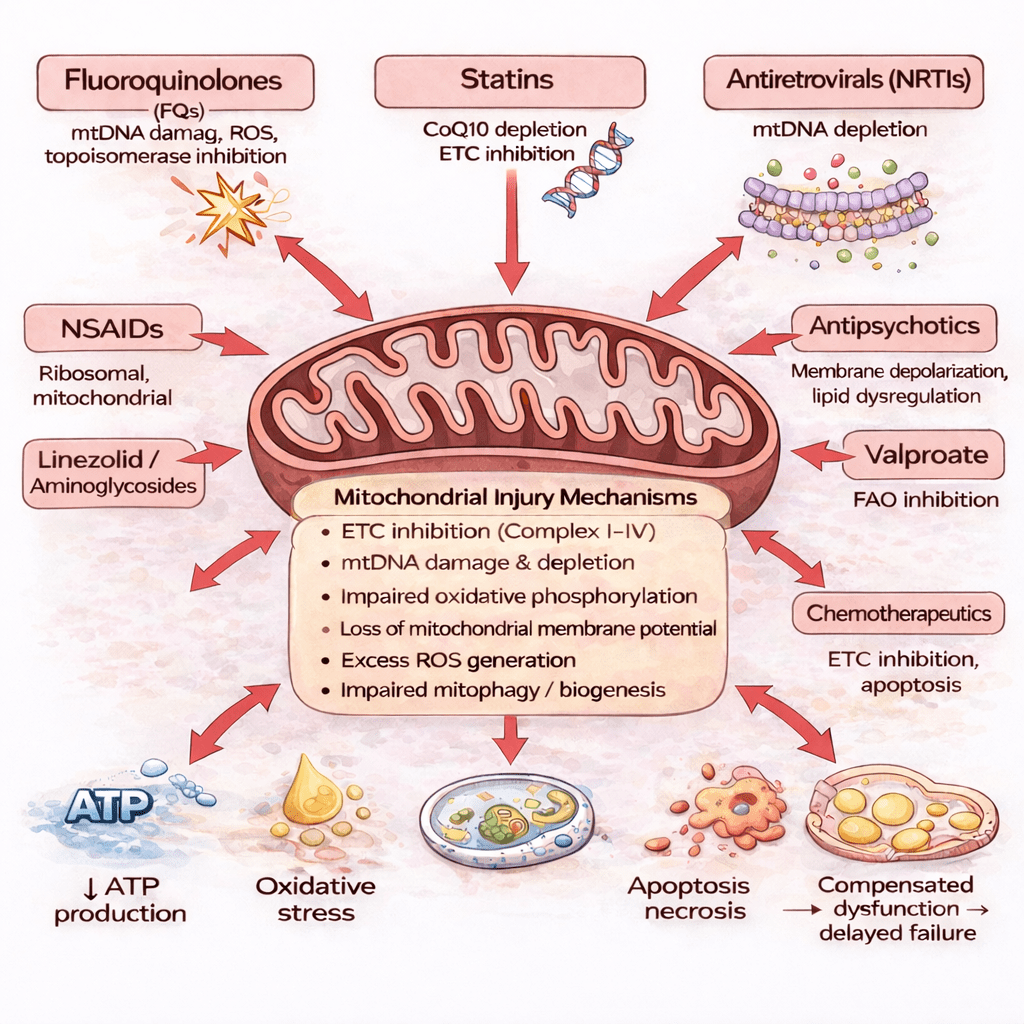

Drug-Induced Mitochondrial Dysfunction (DIMD) refers to a pattern of injury that occurs when certain medications interfere with mitochondrial function — the body’s cellular energy system.

Mitochondria are the powerhouses of cells, responsible for generating energy through processes like oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS), ATP synthesis via the Electron Transport Chain; they also regulate calcium homeostasis, reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, and cell death pathways. When mitochondrial function falters—due to factors like impaired electron transport chain activity, excessive ROS, disrupted dynamics (fission and fusion), or defective mitophagy (selective removal of damaged mitochondria)—it can lead to energy deficits, oxidative stress, and neuronal damage. This dysfunction is a hallmark of many neurodegenerative diseases, often acting as a causative factor rather than a mere consequence, exacerbating synaptic loss, protein aggregation, and cell death in vulnerable brain regions.

DIMD does not usually present as a sudden or dramatic illness. Instead, it often develops quietly and progressively, with symptoms emerging months or years after the original medication exposure.

DIMD is not a single-organ condition. It is a systems-level energy disorder that can affect multiple tissues at once — particularly those with the highest energy demands such as the brain, nerves and muscles.

Fluoroquinolones are the most well-documented example of drug-induced mitochondrial dysfunction.

Why Mitochondria Matter

The Body’s Energy System

Mitochondria are often described as the “power plants” of the cell, but a more accurate comparison is a distributed energy grid. Every organ relies on a continuous supply of cellular energy to maintain structure, regulate signaling, and recover from everyday stress.

Some tissues require far more energy than others. These include:

- The brain and nervous system

- Muscles and connective tissue

- The heart

- The autonomic nervous system

- Endocrine organs

When mitochondrial function is impaired, these high-energy systems are often affected first.

Importantly, mitochondrial dysfunction does not necessarily cause immediate cell death. Instead, cells may enter a state of compensated dysfunction — surviving, but operating below normal capacity. Over time, this reduced energy availability can impair healing, weaken tissue integrity, and disrupt coordination between systems.

This helps explain why individuals may appear outwardly “normal” for long periods, even as symptoms slowly accumulate.

How Medication Exposure Can Lead to Lasting Injury

How Drug Exposure Can Disrupt Cellular Energy

Certain medications are now known to interfere with mitochondrial processes in ways that were not fully recognized when many drugs were first approved.

Depending on the drug and the individual, medication exposure may:

- Interfere with mitochondrial DNA integrity

- Disrupt energy-producing pathways

- Increase oxidative stress within cells

- Impair the cell’s ability to repair and regenerate

In many cases, the body initially compensates for this injury. Mitochondria can adapt, increase output temporarily, or shift metabolic strategies to maintain function. This compensation can mask injury and delay symptoms.

However, compensation has limits.

When energy demand exceeds the cell’s reduced capacity — due to physical stress, illness, aging, or repeat exposure — symptoms may emerge or accelerate. Because this process unfolds gradually, the connection to a past medication exposure is often overlooked.

This is why individuals with DIMD may experience delayed, progressive, and multisystem symptoms that appear unrelated to one another — and unrelated to the original drug exposure.

Why Symptoms Often Appear Unrelated

One Mechanism, Many Symptoms

When mitochondrial function is impaired, the resulting energy disruption does not affect the body uniformly. Instead, symptoms emerge in the tissues that are most energetically stressed or least able to compensate.

This is why individuals with DIMD may experience symptoms that span multiple organ systems, including:

- Neurological changes (neuropathy, cognitive changes, sensory disturbances)

- Musculoskeletal and connective tissue injury (pain, weakness, tendon injury)

- Autonomic dysfunction (heart rate variability, blood pressure instability, temperature dysregulation)

- Profound fatigue and reduced exercise tolerance

- Endocrine and metabolic disturbances

These symptom patterns overlap significantly with many chronic conditions labeled as autoimmune, neurodegenerative, or neurodevelopmental — where mitochondrial impairment often plays a key role

Because these symptoms appear across different systems, they are often evaluated separately. Neurological symptoms are sent to neurology. Tendon injuries are sent to orthopedics. Fatigue is addressed in isolation. Autonomic symptoms may be attributed to stress or anxiety.

What is missed is the unifying mechanism: impaired cellular energy production affecting multiple high-demand tissues simultaneously.

Without a framework that connects these symptoms, patients are often left with a collection of partial explanations rather than a coherent diagnosis.

Why DIMD Was Not Recognized for Decades

Limits of Traditional Drug Safety and Medical Training

Most modern drug safety frameworks were developed during an era when medications were simpler and mechanisms of toxicity were easier to observe. These models focused primarily on acute toxicity, dose-dependent organ injury, and short-term adverse effects.

Delayed, cumulative, or energy-system–level injury was not well understood and was rarely monitored.

At the same time, medical education increasingly emphasized organ-specific specialization. Clinicians were trained to identify disease within defined boundaries rather than to recognize systemic dysfunction spanning multiple systems.

As a result:

- Delayed adverse effects were rarely linked back to prior drug exposure

- Mitochondrial injury was not routinely taught outside of rare genetic disease

- There was no mechanism for long-term outcome tracking

- No centralized registry existed to identify patterns over time

DIMD did not fail to exist.

The system was not designed to recognize it.

Why Patients Are Often Dismissed

When Symptoms Do Not Fit Established Models

Many individuals with DIMD undergo extensive medical evaluation. Standard imaging and laboratory tests may appear normal, particularly early in the course of illness.

When results do not provide clear explanations, symptoms may be labeled as functional, stress-related, or psychological in origin. In this context, anxiety, depression, or emotional instability are often treated as primary conditions rather than as possible consequences of impaired cellular energy metabolism within the nervous system.

It is important to state clearly:

Symptoms associated with DIMD are real, physiological, and explainable — even when conventional tests are normal.

Mitochondrial dysfunction affects how cells generate and regulate energy, not necessarily whether structural damage is visible on routine studies. Without tools designed to assess energy metabolism, these injuries can remain invisible to standard diagnostics.

What DIMD Is — and What It Is Not

Clearing Up Common Misconceptions

Because DIMD is still poorly recognized, it is often misunderstood.

DIMD is not:

- An allergic reaction

- A single-organ disease

- A rare childhood-only genetic disorder

- A psychological condition

- A sign of personal weakness

DIMD is:

- A biological injury affecting cellular energy production

- Variable in severity and presentation

- Influenced by timing, dose, duration, and individual vulnerability

- Capable of producing delayed and progressive symptoms

- Often invisible to standard diagnostic testing

A Note on Individual Vulnerability and Maternal Inheritance

All mitochondria are inherited from one’s mother. This means that baseline mitochondrial function — including energy efficiency and capacity for repair — is influenced by maternal mitochondrial background.

This does not mean DIMD is a genetic disease. Rather, it helps explain why individuals exposed to the same medication may experience very different outcomes. Some may tolerate exposure with minimal effects, while others may be more vulnerable to lasting injury.

Maternal mitochondrial background is one of several factors that may influence susceptibility, alongside age, cumulative exposure, health status, and environmental stressors.

Recognizing this variability helps shift the conversation away from blame and toward individualized understanding.

Why Awareness Matters Now

Why Recognition Changes Outcomes

Improved awareness of DIMD has meaningful implications for patients, clinicians, and health systems.

Earlier recognition can:

- Prevent repeated or compounding injury

- Reduce unnecessary testing and misdiagnosis

- Improve patient validation and trust

- Support more appropriate monitoring and care

- Enable research into long-term outcomes

DIMD highlights a gap between modern pharmaceutical complexity and outdated safety and training models. Closing that gap requires shared understanding.

What You Can Do Next

Moving Forward With Information and Purpose

Understanding DIMD is the first step. What comes next depends on who you are and what you need.

If you are a patient or family member:

- Learn common symptoms and warning patterns

- Document medication exposures and timelines

- Share this information with your care team

If you are a clinician:

- Consider energy-system injury when symptoms span multiple high-demand tissues

- Recognize that normal tests do not exclude mitochondrial dysfunction

- Stay informed as guidance continues to evolve

If you are a researcher or advocate:

- Support long-term tracking and outcome research

- Contribute to data collection and awareness

- Help build the infrastructure that has historically been missing

Understanding DIMD is not about assigning blame.

It is about recognizing reality — and building better systems in response.